What You Need to Know About Body Mass Index

Written by Michael Hunter, MD, and originally published on 27 September, 2021 in BeingWell.

THERE IS NO “PERFECT WEIGHT” that applies to all of us. Body Mass Index (BMI) measures how healthy your weight is, based on your height. BMI has become a standard health assessment tool in my radiation oncology office and many healthcare facilities. But is BMI outdated?

We begin with a definition of BMI. Body mass index measures body fat based on height and weight that applies to adult men and women. If you want to calculate your BMI, there are many online resources. For example, the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute offers this remarkably easy-to-use one:

Belgian mathematician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet developed the Body Mass Index in 1832. He aimed to estimate the degree of overweight and obesity in populations quickly. This determination would help government optimize health resources and financial allocations.

Quetelet did not view BMI as particularly useful for studying individuals; to him, it provided a snapshot of a population’s general health. It is impressive that nearly two centuries later, we still use BMI.

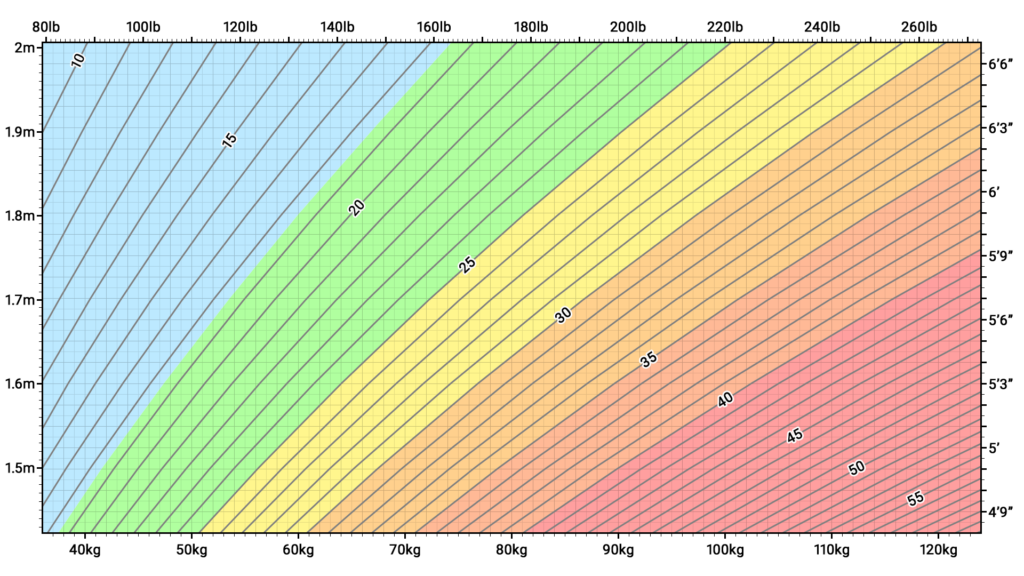

BMI centers on a mathematical formula that divides an individual’s weight (in kilograms) by height (in meters squared). Not a metric system user? You can calculate body mass index by dividing weight in pounds by height in inches squared and multiplying by 703:

- BMI = (weight (lbs) / height (in2)) x 703

Better yet, use an online BMI calculator, such as the one provided above. Once you have your BMI, you can compare it to the BMI scale:

- BMI < 18kg/m2 is underweight

- BMI 19–24.9 kg/m2 is normal

- BMI 25–29.9kg/m2 is overweight

- BMI 30–34.9 kg/m2 is class I obesity

- BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2 is class II obesity

- BMI 40 kg/m2 and above is Class III obesity

Image by nagualdesign, shared under CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

While there is no perfect weight or body mass index that is universal, BMI provides some insight into your risk of health-related problems. But does the BMI represent an oversimplification of what being healthy represents?

In recognition of different statures worldwide, some countries have modified what defines normal. For example, Asian men and women have a higher risk of heart disease at a lower body mass index than non-Asians.

Using the World Health Organization (WHO) Asian BMI risk cut points, the three categories are 18.5–22.9 kg/m2 (normal weight), 23–27.5 kg/m2 (overweight), and ≥27.5 kg/m2 (obese).

Is there value in knowing one’s BMI? A 2017 study showed that those with a body mass index of 30 or greater (obese) had a 1.5 to 2.7-times higher risk of death over a 30-year follow-up. A separate 2014 study demonstrated a 1.2-fold increase in early death from all causes and heart disease compared with those with a normal body mass index.

For the 2012 study, death advanced by 3.7 years for those with class II and III obesity. These weight classes advanced cardiovascular-specific mortality by a range of 1.6 years (for class I obesity) and five years (for class III).

Compared with normal-weight, all-cause mortality rates appear higher for underweight adults older than 45 years, with cardiovascular death risk rising for underweight adults older than 65 years. However, there appears to be no increased mortality risk among underweight persons in any Asian sex-ethnicity group (Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, South Asian).

BMI is flawed

Body mass index does not account for age, genetics, sex, lifestyle, medical history, or many other factors. Its use may cause us to lose focus on other necessary measures of health. For example, BMI has nothing specific to say about blood sugar, cholesterol, or blood pressure. It does not address diet or living environment.

And what about the differences in body composition between men and women? BMI does not distinguish between men and women. Males have more muscle mass (and less fat mass) than do women. In my 30s and 40s, I spent a fair amount of time doing resistance training. As I had more muscle, my BMI made me appear obese (even though I was far from it by any other measure).

In addition, as we age, our body fat increases, and muscle mass drops. It doesn’t account for who has an apple body shape and who has a pear shape. Individuals with fat stored around their abdomen (apple shape) have a greater risk of chronic disease than those stored in their hips, buttocks, and thighs, known as gynoid or pear-shaped body types.

Did you know that some studies show a BMI between 23 and 29.9 can be protective against early death and disease?

In summary, BMI (while flawed in many ways) provides a general estimate of health risk. Body mass index should not be the only measure of your health.

Thank you for joining me today.

Dr. Michael Hunter has degrees from Harvard, Yale, and Penn.

He is a radiation oncologist in the Seattle area.

You can find him regularly posting at www.newcancerinfo.com.